I don’t remember ever being told my father was dying. I must have been too young when I internalized this information. I think I always knew he was sick, and since my dad was an AIDS educator, it wasn’t like I didn’t know what the disease did.

It was the 1990s. We were only beginning to knew what AIDS was, and at 8 years old, I only understood what it had done to my father.

My memories of these days are so scattered, and I try to pick up the pieces, scrambling them together like a puzzle made of my own sadness.

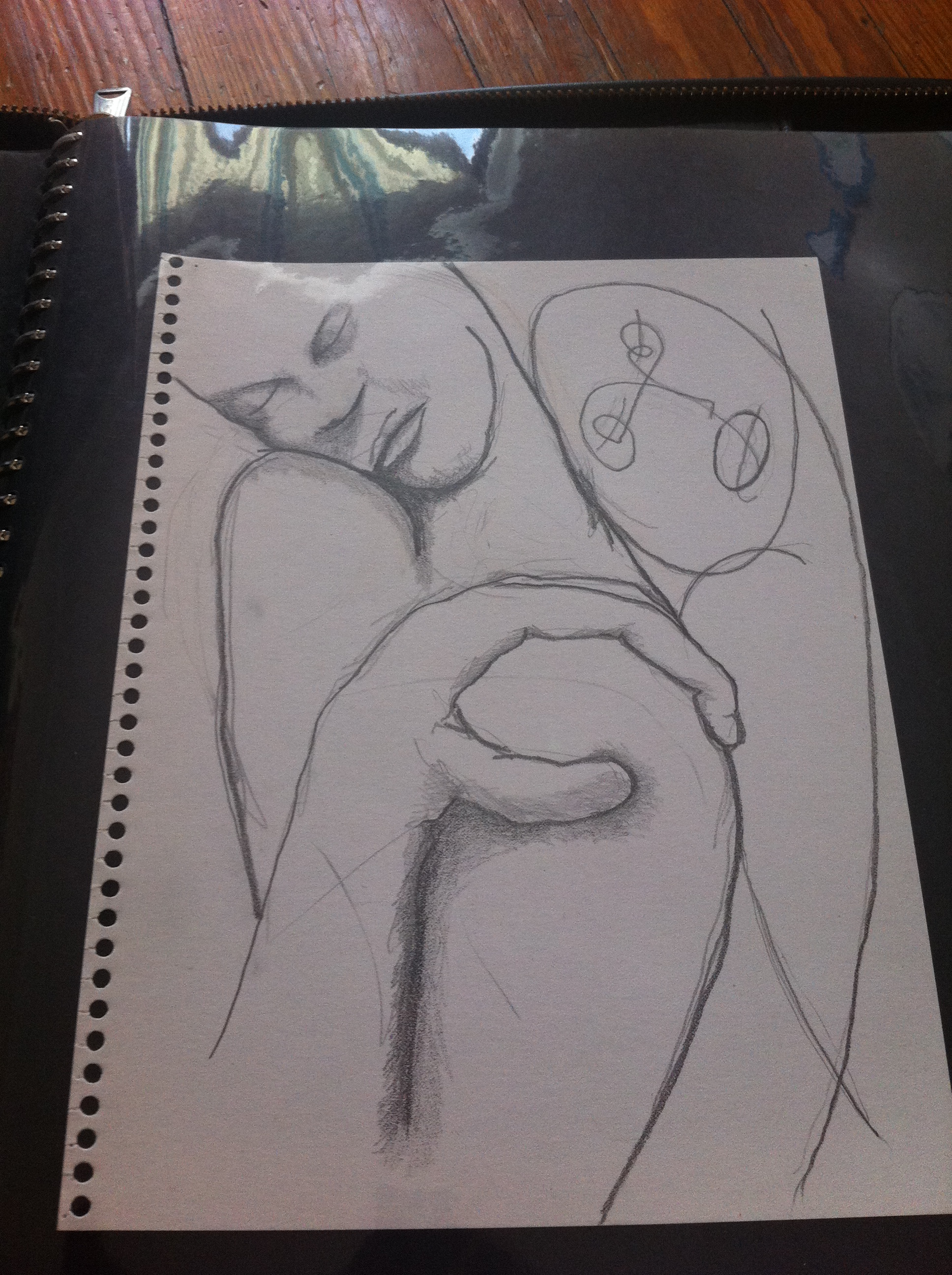

I’m still missing some of the pieces – and as an adult I am discovering that the process of getting to know my father nearly twenty years after his death is something I am going to have to fight through. I have letters, written to him, and written from him to others. I have his artwork. I have his writing. I have the play he wrote about his disease.

But I will never remember what he smells like. How do I grab hold of his smell, or his tone when he was happy? The question I begin to ask myself is not “who was he?”, but sometimes “Who am I?” in the context of my lineage.

People tell me I look like him. I have been told that I dance like him once or twice. But I cannot draw like my father, and our writing styles are vastly different. Where does the person I have become line up with the person that he is, and how do I integrate these things into a whole?

When all you have is fragments, where do you begin?

The discovery of who my father was is slow.

Whether or not we realize it, our parents are integrated into our identities at early stages in our development. But there was no father to take with me to the father daughter picnic for father’s day, and I remember having to explain myself whenever a classmate at a new school would ask why I wasn’t making my dad a card.

As adults, we’re expected pretty frequently to identify with our families – especially in highly socialized rituals like weddings. When I got married last year, strangers would ask, “is your father going to walk you down the aisle?” or say, “Oh, your father is just going to love lifting this veil off your face!”

I’ve never been a Daddy’s Girl. I don’t even know what that means. I do know that I spend a lot of time trying to figure out how to acknowledge and remember a person who I don’t really know. This year I’m forming an NYC AIDS Walk group in his memory – to walk in his honor and raise funds to fight the disease which killed him. But I don’t want to know my father through his disease. I don’t want to have him be just an illness. I want him to be my parent.

The problem is that even when I ask the people who knew him best about his life, they can’t tell me about the relationship we might have had because none of them are his child. These splinters of memory – reading books about hippos, playing rocketship/astronaut games before going to sleep (and sharing my bed with him when I stayed the night), having my art hanging on the wall – a child’s sketches, next to his artwork during a showing— reading his dedication to me in the play he wrote. These are the things I can cling to.

But they’ll never be enough.

I don’t know if this is what it’s like for everyone when they lose a parent – but I know that I still grieve 20 years later, in part not because I miss him, but because I miss what he could have been in my life. I miss the may-have-been moments.

As a child I remember that I clung to the idea of his physical remains – his ashes, because they were the only reminder I had that he had been there at all. I sometimes envy the people who have gravesites to visit, because at least then there is an acknowledgement outside of their memories – a physical space to occupy when you wish to remember. I don’t have a gravesite, but I do have physical touchstones. As a historian, I suppose it does help me to have these artifacts of his life. I own his archive.

I didn’t know, for example, that my father could read German until I found letter written to him exclusively in German. I didn’t know that his artwork wasn’t always abstract, and that the things I love in art are influenced by the work he did when I was around him. I don’t know how I’m like him, but I want to know. I remember going with him to teach AIDS education classes to adults – I have letters thanking him for his teaching, and these are the things I choose to carry with me. I haven’t done the work in a long time, but I think it may be a way to connect with him – something which I did with him before that I can carry on as an adult. The disease is so different now, but the reality remains the same.

It happened to me, it has happened to others: their parents die from AIDS, but instead of everyone understanding it like they would cancer or another terminal illness, the sideways glances of misunderstanding cloud their faces. The politics of sex education and gay rights muddle the story of my past, and I am forced to politicize the very nature of my identity. The teddy bear gay pin sits in my jewelry box. The ACT UP pin sits next to it. The photos of drag queens and letters from family sit in my office, and I need to find a way to synthesize the historical image of my father with the reality. I need to understand where I came from without forgetting what I already know.

He was Tanya Ransom, a drag queen. He was Michael, an artist, educator and playwright. And he was a patient. And he was my father.

N.B.: If you would like to donate or walk in the AIDS Walk Team I have begun, it is team 4884!